Scientists are trained to run experiments, analyze data, and present their results to colleagues. What scientists are not trained for is communicating the same information outside of their scientific circles.

This skill is necessary, especially since the U.S. EPA recently issued a proposed rule that could revise the risk evaluation process for existing chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act, or TSCA.

“This is one of the things I love about being trained in science, because we’re taught to put our ideas out there and ask that people understand it as well as we poke holes at it so that we can understand that we’re all putting the best information out there,” said Suzanne Hartigan, the American Chemistry Council’s senior director of regulatory and scientific affairs, at the Personal Care Products Council’s Science Symposium and Expo last week.

Some of the proposed changes include modifying the risk assessment for each case of the chemical’s use, as the rule currently assesses the chemical’s risk. The proposal intends to clarify how the EPA will determine occupational exposure controls such as personal protective equipment. The legislation also aims to clarify the agency’s authorized purpose in determining which circumstances of a chemical’s use and its exposure routes and pathways it will deem in a risk evaluation.

The proposed regulation’s comment period ends Nov. 7, and as of Wednesday, it has received 1,515 comments. However, it’s been a struggle for chemical makers to communicate what they’re assessing, what it means for potential regulatory action, particularly under TSCA, and how the general public interprets it.

She pointed out the importance of why chemical and personal care product manufacturers and suppliers must learn to explain the science behind the data and how it can impact TSCA regulation.

How to translate the science

Science alone doesn’t drive sound policy, but if scientists don’t have a way to convey its importance and make it understandable, they risk reducing its impact, Hartigan said.

“We’re trained to understand the data and information and we do present, but we’re often presenting to each other,” Hartigan said. “But the further along you go in your career, you have to communicate this information to other people who need to understand the benefit of what you’re doing and to different audiences.”

Communication is useful when requesting funding, communicating with customers, and engaging with government officials regarding legislative or regulatory proposals and their potential impact on the chemical manufacturing industry.

The elevator speech is one way to explain what a company is working on and why it matters, Hartigan said. Another way is to explain it as if the person is a parent or grandparent who’s not a scientist.

“Someone who doesn’t understand or have the background that you do and being able to explain that to them is a skill set,” Hartigan said. “It’s not easy, and it really requires you to have a fundamental understanding of what you’re working on.”

Miscommunication can also cause confusion and skepticism, she added. If people do not understand the science that is being explained to them, they’ll assume something is being hidden when that’s not the case.

While it can be frustrating, she adds that it’s important to view communication as a challenge and an important skill set to develop, rather than a problem. Moreover, the stakes are high.

“Public trust is important,” Hartigan said. “Regulatory credibility relies on our ability to communicate the science that we’re doing to underlie regulations, and it can impact market stability as well.”

Interpreting the science in the TSCA context

The EPA has made other policy changes that may have burdened itself, Hartigan said. The agency acknowledged that it’s having trouble keeping up with accomplishing the risk assessments, including considering every condition of use in every exposure scenario.

The EPA provides further guidance on the TSCA risk evaluation process for existing chemicals and the various specific uses on its website. Unlike other chemical legislation for which the various uses of the substances are well understood, chemicals under TSCA regulation is not a one-size-fits-all policy.

“It’s the gap filler, catches all the other conditions that’s used largely in industrial, but have the potential to be used in other products that aren’t regulated elsewhere,” Hartigan said.

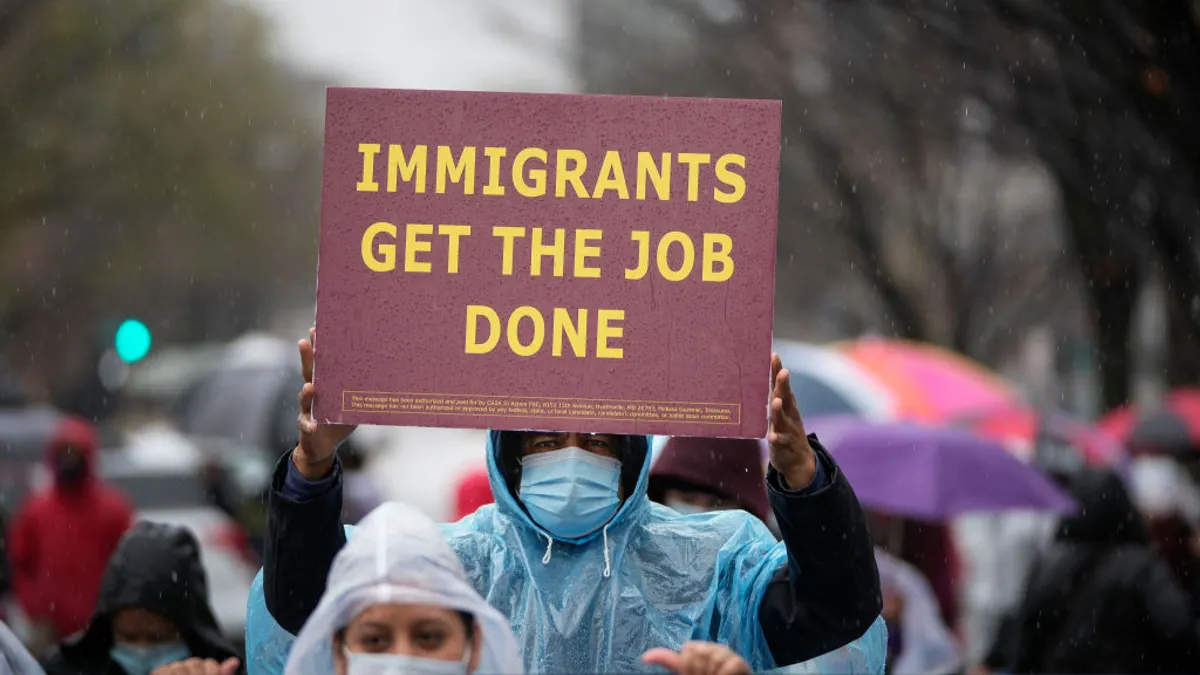

The conditions of use include considering worker scenarios, which may differ by jurisdiction. A manufacturer may have diverse uses for a chemical or use various amounts, depending on the product, such as plastics.

It may also include different sectors, as exposures are distinct and there is a set of controls expected across the industry that the EPA may not know about until they are informed.

Additionally, there are uncertainties and limitations associated with some of the data, which stakeholders will need to explain.

Understanding the data based on risk assessment science and information — the hazards, exposures — feeds into the regulatory decision, Hartigan said.

“Every step of the way requires clear messaging,” she said.

While chemical makers are in a place where the TSCA rule proposal may return individual risk determinations back to the law’s 2017 version, it doesn’t solve all the risk communication problems that come out of the 700-page assessments and multiple conditions, Hartigan noted.

“How do you explain that? How do you make that data information available to different types of folks?,” Hartigan said. “I think we’ve still got a long way to go.”