A maintenance procedure involving a gas isolation valve may have led to the Aug. 11 explosion at U.S. Steel’s coke works plant in Clairton, Pennsylvania, that killed two people, according to the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board’s initial report released Sept. 29.

The Clairton facility processes raw coal into coke, which is used as a component in making steel and iron, according to the CSB press release. The facility is located about 15 miles outside of Pittsburgh and spans 392 acres, employing nearly 1,300 workers.

“Tragedies like this must lead to change,” Board Member Sylvia Johnson said in a statement. “Our investigation will identify not just what went wrong, but what must be done to ensure workers across this country are protected from similar hazards.”

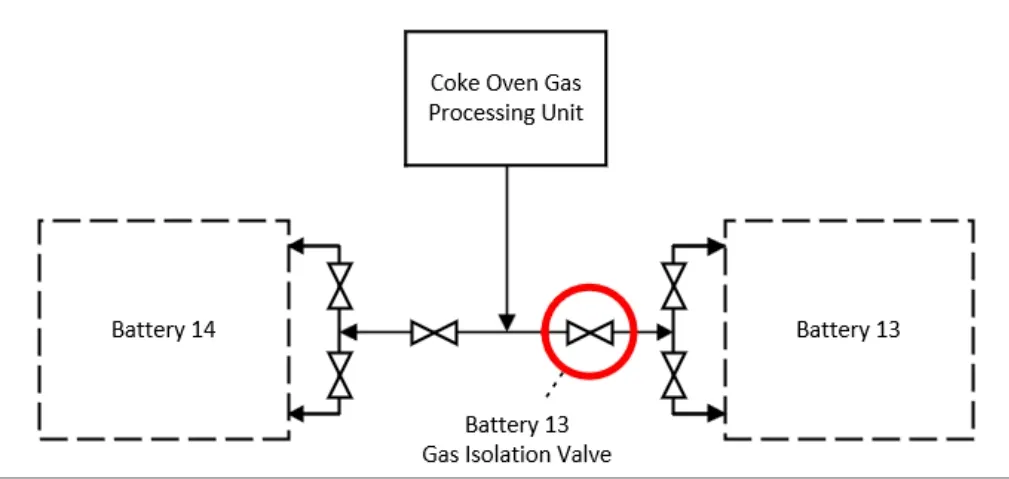

The process occurs in six coke ovens, which are stacked in rows and connected by a shared wall, operating as one unit called a battery. The unit involved in the explosion, which the company dubbed “13/15 Battery,” comprises of three batteries located close to each other, according to the report. The 13, 14 and 15 batteries were built in the 1920s and underwent a coke oven rebuild in 1952. Batteries 13 and 14 underwent a second rebuild in 1989, while Battery 15 shuttered in May 2024.

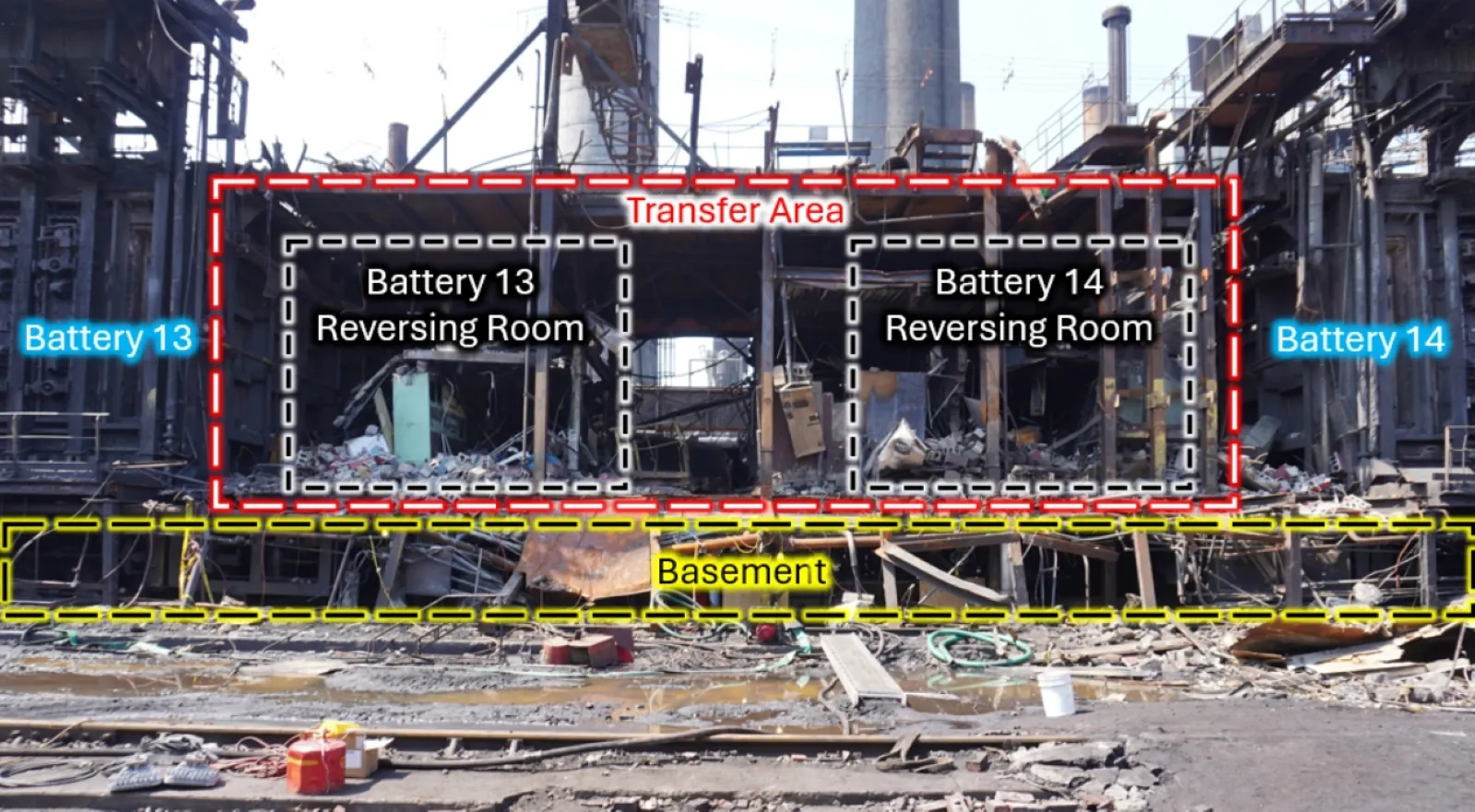

The batteries are separated by a transfer area, which contains control and break rooms, personnel shacks and entrances leading to a basement shared by Batteries 13 and 14. The area also had a staircase that led to the top of the battery. U.S. Steel workers told the CSB that coke oven gas residue builds up at the bottom of piping and in valve seats.

Coke oven gases comprised of various amounts of hydrogen, methane, nitrogen and carbon monoxide, mixed with smaller amounts of other substances. Coke oven gas is also highly flammable, toxic, colorless, and has a rotten egg odor. Exposure to the hazardous substance can cause asphyxiation.

Events leading up to the blast

About a month before the explosion, U.S. Steel discovered a coke oven gas leak emanating from a valve cracked near one of its components. The cracked valve was downstream of Battery 13’s isolation valve, an 18-inch cast-iron double-disc gate valve manufactured in 1953 and refurbished in 2013. U.S. Steel temporarily repaired the cracked valve to prevent flammable coke oven gas from leaking into Battery 13 and 14’s basement.

The steel manufacturer made plans to replace the damaged valve, along with at least three other valves, by isolating Battery 13 from the coke oven gas supply.

U.S. Steel held a meeting on July 28 to discuss the scope of the work and review the hazards for Battery 13’s maintenance outage that was scheduled for Aug. 19.

On Aug. 11, the day of the explosion, the steel maker decided to exercise Battery 13’s gas isolation valve, which involves closing and reopening to help separate the downstream equipment and piping. A company supervisor called on one employee from MPW Industrial Services to provide a pump to flush the valve seat. MPW did not participate in the July 28 maintenance outage meeting.

That morning, three U.S. Steel workers moved forward to Battery 13 and 14’s basement, where the isolated valve was located, to proceed with the valve exercise. Three MPW employees prepared their equipment to inject water toward the valve seat through a cleanout port from a hose connected to a positive displacement pump.

Each worker had their own carbon monoxide monitor and one MPW worker carried a four-gas monitor to detect oxygen, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide and flammable gas. Data recovered from the devices showed they alerted the workers to the presence of toxic gases. One MPW employee told the CSB that they noticed water leaking from the valve’s cap component. The employees also heard a pop sound and one worker reported smelling gas.

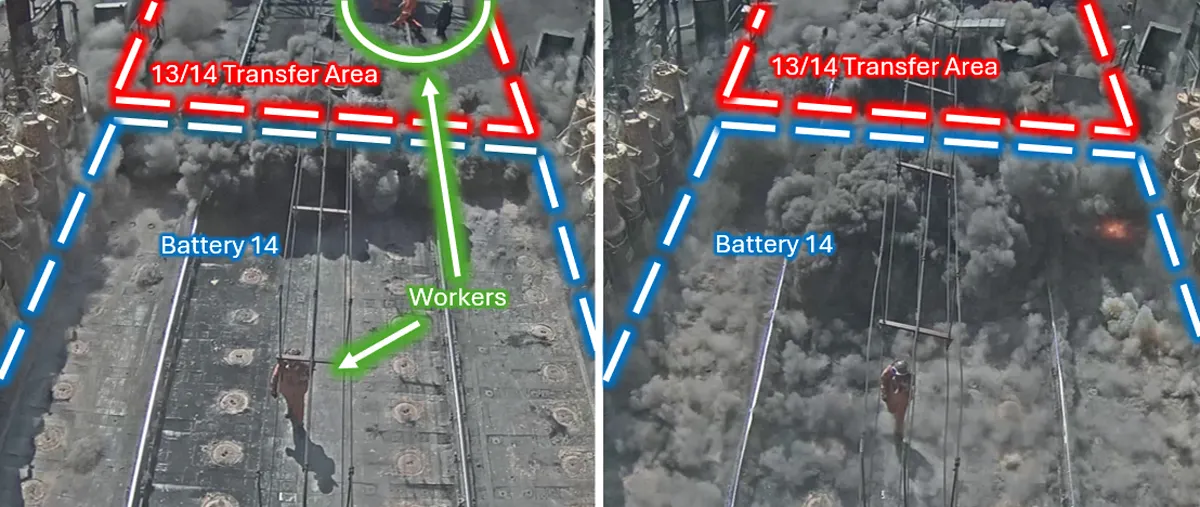

The U.S. Steel supervisor ordered the workers to evacuate the basement and the company’s employees then called for evacuating Batteries 13 and 14 via radio or verbally. The explosion occurred less than one minute after workers made the radio evacuation call.

At the time of the explosion, at least 22 U.S. Steel and three MPW employees were working on Batteries 13 and 14. Additionally, at least four people were on top of Battery 14 and the transfer area, including an Allegheny County Health Department field compliance engineer and their Veolia escort, who were inspecting the unit for air quality compliance.

The blast killed two U.S. Steel workers and seriously injured and hospitalized five others, including an employee of Veolia Water North America Operating Services, according to the report. Six additional workers — five of whom work for U.S. Steel and one employed by MPW — were treated for minor injuries and did not need hospitalization.

One of the workers killed, Timothy Quinn, was a second-generation steelworker and worked at the Clairton plant for nearly two decades, Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro said at an Aug. 12 press conference. The family of the second worker who died wished to keep their identity private, Shapiro added.

The explosion also damaged the structures within the transfer area, including both the Battery 13 and Battery 14 reversing rooms.

After the blast, the CSB recovered Battery 13’s isolation valve and found its body split open by a crack, which the CSB said “failed catastrophically.” The agency also recovered at least nine additional valves of various sizes used for the battery oven gas systems from the transfer area, four of which were also damaged. However, the CSB has not determined whether the valve failures occurred before or as a result of the explosion.

The aftermath

The investigation is still ongoing as CSB continues to gather evidence and evaluate several key areas, including the cause and source of the gas release. The agency will also analyze the metal alloy properties of cast iron valve components, U.S. Steel’s use of cast iron materials in its coke oven gas systems, valve maintenance and exercising policies and procedures, and the company’s safety management systems. CSB did not disclose when the final report will be released.

United Steelworkers Local Lodge 1557, which represents U.S. Steel workers at the Clairton plant, established a GoFundMe page aiming to reach $100,000 to support the victims and their families following the explosion.

“We appreciate the CSB’s careful attention to this incident and will continue to work with its representatives in Clairton as it builds out its final report,” Bernie Hall, USW District 10 director, said in an emailed statement. “We owe it to our fallen siblings to not only learn everything we can about what may have contributed to the explosion on Aug. 11, but to carry those lessons forward so that all workers can be safer on the job.”

U.S. Steel said in an Aug. 15 statement that it worked with other agencies, the United Steel Workers union and third-party experts investigating the explosion

CSB’s initial findings aligned with U.S. Steel’s findings and remain committed to working with the agency to complete the report, Andrew Fulton, U.S. Steel’s media relations representative, said in an email. The facility remains operational and the coke has been removed from the ovens and placed on a hot idle state to preserve the ovens’ integrity.

“We thank the CSB for their diligent work in examining the circumstances of the Clairton incident,” Fulton said in a statement. “Concurrently, we are enhancing our safety protocols in line with the findings. Throughout this process, our unwavering focus remains on prioritizing the well-being of our employees and their families. As always, Safety First remains our core value.”

Editor’s note: The story has been updated to clarify that the CSB has not yet determined the potential role of a cracked valve in the explosion.