The manufacturing industry has long bemoaned the decline of its workforce. Yet today’s manufacturing educational pathways look much like they did in the ‘80s, when hiring numbers began declining.

Apprenticeship programs remain scarce, with just 678,000 apprentices registered nationwide (in comparison, Germany’s labor force is less than a third of the U.S.’ yet maintains 1.22 million apprentices). And according to one Dewalt survey, students believe that trade schools are costly and offer limited networking opportunities.

One underrated option may hold the most promise for workforce growth: the local community college.

That’s according to a series of reports by The Rutgers Education and Employment Research Center released in October, which examines the “hidden innovative structure” of America’s community colleges.

Community colleges excel in ways conducive to a successful manufacturing career, said Shalin Jyotishi, founder of the Future of Work & Innovation Economy Initiative at think tank New America.

The schools are accessible, closely plugged into the local manufacturing industry and usually more affordable. For many people, Jyotishi said, a community college is the best way to enroll in a program that offers all the benefits of an apprenticeship.

“An apprenticeship program is the closest possible coupling between education and work experience since the Babylonian times. It’s largely considered the gold standard in workforce education. The problem is, in the U.S., only 2% of our students go through apprenticeship programs,” Jyotishi said.

Apprenticeship coursework is often exclusively aligned with specific occupations and not transferable to four-year universities. Community colleges allow students to enroll in credit-bearing courses, which can open future doors to opportunities in advanced manufacturing and beyond.

What makes community colleges unique

Unlike many higher education institutions, community colleges are able to develop, tailor and put specialized courses in manufacturing on offer at a quick pace.

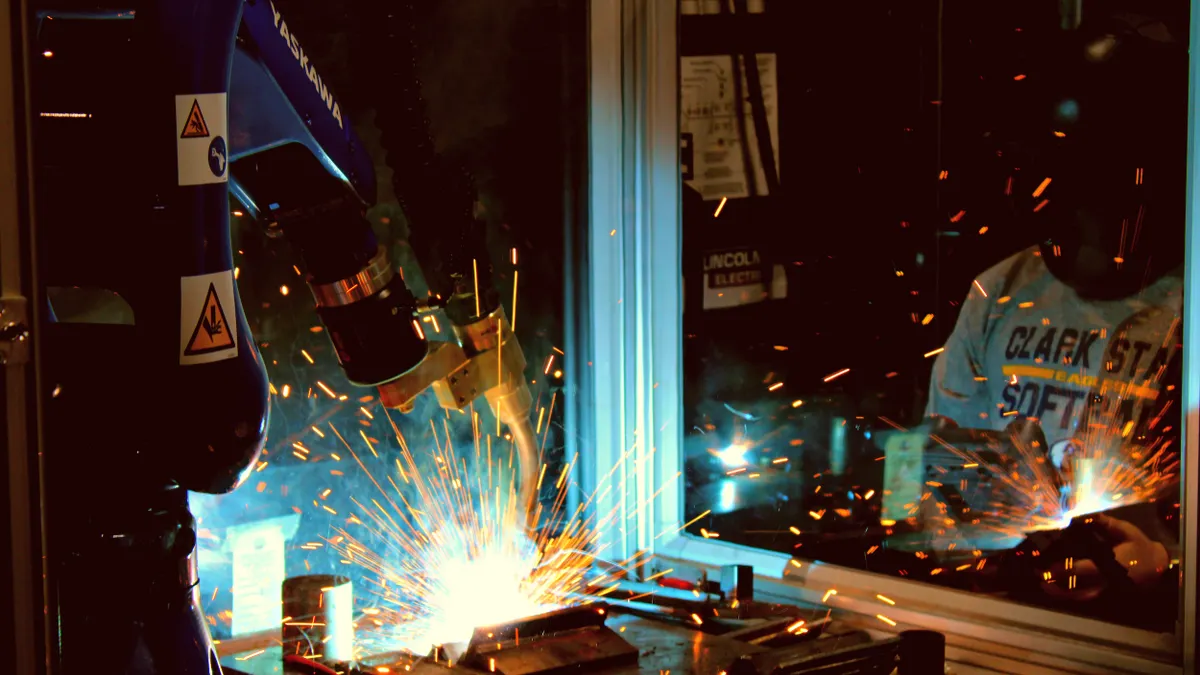

Students at Ohio-based Clark State College, for example, can obtain up to 14 manufacturing certificates, which can be applied toward a Bachelor of Applied Science degree in Manufacturing Technology Management.

President Jo Blondin said much of this is created according to the Developing A Curriculum model, which centers industry input.

For instance, the college organized a workshop with a core group of subject matter experts representing Ohio Laser, Resonetics and GE/Unison to develop its most recent certification. This led to the Laser Materials Processing/Photonics certification, which Blondin said is “extremely important for base contractors, both inside and outside the fence.”

Simultaneously, Blondin said, the college’s engineering tech coordinator organized another advisory meeting to “obtain key insights to evolving advanced manufacturing skills desired by industry partners.” This included participants from Amazon, American Pan, Honda, LH Battery, Rittal, Sweet, Topre and Valco.

“If a business comes to us and says, ‘We really need this training,’ we're going to move heaven and earth to make it happen. And I would say that most community colleges that have a strong workforce development focus take that approach,” she said.

Maintaining excellent industry relationships isn’t just a boon for the curriculum, it also allows colleges to offer training with a degree of job placement support.

While still employed at Honda, Scot McLemore helped develop an apprenticeship program for manufacturing in which students could interview for and do paid work at a local advanced manufacturing employer for three days a week.

And while there was no guarantee, “it was the intention of both the company and the college for that student to then be employed with that company at the end of that apprenticeship,” said McLemore, who now serves as the vice president of the Office of Talent Strategy at Columbus State Community College. At worst, the student walked away with a network, real-life experience and skills tested in a live manufacturing environment.

Community colleges also offer something that many apprenticeships do not: following their coursework, students have the flexibility to move away from manufacturing.

“Some of these students are going to be transfer students that go on for a four-year degree. The others are going to go directly into industry either with their associate’s degree or noncredit learning and completion certificate,” said McLemore, referring to the noncredit bearing coursework that manufacturing training is usually categorized under.

“Our job here is to serve the individuals in the Columbus area and be the front door to their success,” he said.

That commitment to serving the community is baked into the community college ethos, said Blondin, and it applies across industries.

Just three years ago, Clark State’s nursing program enrolled 350 students. Today, it has 786 students in classes.

That’s a direct result of increased demand from local hospitals and healthcare providers, said Blondin, adding that demand from manufacturers is also growing.

According to a Rutgers report, community colleges are “filling knowledge and coordination gaps among local manufacturers and acting as ‘innovation brokers’ by linking their programs to the needs of local employers.”

“We do see a general trend for community colleges to be more focused on workforce issues in their local communities,” said Michelle Van Noy, director of the Rutgers Education and Employment Research Center.

One of the reasons that community colleges can mobilize the faculty and resources at their disposal is because they don’t have the kind of “conflict of priorities” that faculty at research universities might have, according to Jyotishi.

“Faculty are able to work with employers, because that is the sole mission of community colleges. They don't have to balance research with teaching. They just do the teaching,” said Jyotishi, while acknowledging that community colleges are not a monolith.

There’s also the fact that the “noncredit” nature of many manufacturing programs allows “faster time to program creation.” While credit-bearing programs have to move through faculty senates and the accreditation process, their “noncredit” counterparts allow colleges to quickly meet the customized training needs of manufacturers, Jyotishi said.

“It may not happen in two hours, but in 48 hours, we could get something going,” Blondin said.

The community college-manufacturing pipeline

In the United States, people seeking a manufacturing career have “too many options” when it comes to certifications and credentials, Jyotishi said.

According to Credential Engine, there are more than 1 million unique credentials available in the U.S. across sectors including IT, healthcare, manufacturing and more. This, coupled with the fact that not enough data exists on which certifications lead to better employment outcomes, means students must often make difficult choices with little guarantee of results.

“In other countries, there's much more sophisticated mechanisms to curate pathways into jobs. For us, it’s the wild west,” Jyotishi said.

Manufacturers can help develop a skilled workforce by teaming up with their local community college on coursework development, or even offering a work-based learning arrangement that benefits both the student and the manufacturing business.

“I think that everybody — from the CEO to the plant manager to the HR director — should know their counterparts at their local community college, so they can make sure that that's a great relationship,” Blondin said.

She added that community colleges should stay connected to their local legislators, for whom workforce development is top of mind.

“When you talk to anybody, of any party, they will say the number one issue, of course, is workforce.”